Day 1:

A little girl spat on my shoes. While it didn’t actually hit but just sorta fell between them to the ground, I gave her a shove in the chest with my right hand. I wanted her to smash backwards into the ground and stay planted there, but she shot back up unexpectedly and held me by the sleeve. Grabbing her by the shoulders, I tried shaking my arm loose, but her skinny hands had more strength than you would expect.

In no time at all, the people who had been milling around Svornosti Square had already surrounded us. A few of the girls began to whistle as if they knew the one clutching my sleeve. The girl being rooted for twisted my sleeve tighter. The crowded around us edged closer as if they had all been waiting for something interesting to finally happen in the city square. Three dollars is nothing. Just about then I wanted to throw out some money, but the unfamiliar feeling of being in a conflict kindled my anger.

At the same time this girl who nobody had yet torn off of me stomped down on my toes with all of her strength, I slapped her across the face. In a moment of surprise, the confused and embarrassed girl’s hand flew to her cheek.

“Helena!”

A voice called out from among the tourists. Terrified, she turned in the direction of the voice. A fiery looking old woman stood shaking a fist at the girl. She made a move to snatch the backpack from my shoulders and make off with it. “No, not that!” The words flew out of my mouth in Korean. The next thing I knew, I was on the ground with my backpack beneath me like a soldier shielding others from a grenade blast and pulling with all my strength.

Since she couldn’t wrestle it away, she took off with the scarf from my neck instead. Exhausted, I spread my legs across the cobblestone. The shoes the girl shined were a mess and one of the buttons on my shirt was now missing.

When she came––a girl no older than ten––and stood beside me, she started to say my shoes were beautiful. I couldn’t help feeling annoyed, so I walked away. Still talking, she pulled out a dingy rag from her bag and went straight to polishing my shoes. The word beautiful was clearly not the word to describe my old, worn shoes. More annoyed, I stood up to get away from her, but she held out her hand in front of me.

I scowled and just shrugged my shoulders. Three dollars. She calmly pointed to my shoes during her request, meaning to say that it was the price for the shine. I shook my head. She spread the corners of her mouth into a wider smile and repeated. Beautiful. Three dollars. Without acknowledging her I began to walk away, and that was when she spat, when from her palate she heaved up some grossness resembling phlegm. Girl, you chose the wrong person to mess with today.

In an open-air cafe near the square, I order a Czech beer––Pilsner Urquell. Finding a beer I drank so much of back in Seoul is like stumbling across another Korean in exile. But of course, this country has the beer’s hometown. The squash-colored beer which is this country’s specialty arrives in an elaborately cut crystal mug. Cold, slightly bitter, and just the thing to wash away my dirty feelings. The bitter beer goes down my throat with a sting. And then, Ahhh. I exhale.

“You’re pretty tough. Not even one tear?”

A tough person. At the words I patiently clench my teeth and I turn to look at my backpack spread across the chair. If I were really a tough person, I wouldn’t have come all the way to this country. By now, I had all but known that the time for compliments, criticism, encouragement, and burdens had all come to an end, and it was all because of my father.

I swallow the words echoing inside me along with my beer. Because of you, there was never anything I could do—only things I had to do. I never existed here. All that’s left of our relationship is a pain piling up until the day it’ll be erased when we both die. I’m leaving you here and I’m just gonna go back alone. I squeeze the mug tight. The cool touch of the crystal was comforting. Gothic, baroque, rococo, renaissance—the finely cut stone-walled buildings all stand as if called together. Among the architecture, I think of someone who never had anything.

Cesky Krumlov. I came by train on a trip to this tiny village out of a fairy tale. I climb the observatory and look down across the red-roofed village. Will I ever have the chance to come back someday? Of course not…but if I did, it wouldn’t be with the dead fossil I came with this time but somebody living. The little girl will soon come to learn that life isn’t about a searching through street markets for things you can’t have.

Soon, tourists walking to see the Moldau River begin gathering in the center of the city. For the most part, the city was built hugging the river, so traveling along its banks is an interesting way to explore the city. The bustling mass is prepared to praise the beauty of the river as it curves like the waist of a slender woman.

With the setting of the sun, even more people appear along the banks. As the darkness deepens, people who had been seated on the banks stand up one by one. They’re looking for a place more suited to the darkness, and the excitement of the search is etched onto their faces. With a restless expectation to the warm night air, people file off as they drink their alcohol and head out like bodies warmed for spreading love.

Pinwheels spin between couples kissing deeply. A man casts a sideways glance at a giggling group of girls. My eyes meet those of scruffy man lying on the ground. From his posture, he resembles all the dogs scattered along the stairs. I look away from the man and stare at a dog. Every dog in this country is old. Only if you’re old do you have power over your periphery. But even if I wanted to, I couldn’t will myself to be older.

The man looks more worn and drained than the dog. I want to get away from this seat. I know that stare. It starts with an innocent look but ends with some form of violence brandished suddenly. But it’s just a thought. And so, I stayed seated, staring out into the streetlights reflected in the river.

Something shimmers in the water. A girl’s face. My scarf wrapped around the neck beneath the smiling face, long hair covering half the face and trembling in the current. My thoughts are thrown into confusion. This is what it means to travel––forgetting daily life. For these five days of vacation, I’m joining the class of those with boarding passes.

Thinking about the events of tonight, my two faces are reflected in the mirror. In the mirror set deeply into the wall of a hospital bedroom. In the soft, warm lighting of a restaurant’s bathroom mirror. My nights pass between both mirrors and force out the darkness.

Stuck watching over the dying. And living and to prepare food for a person to join me someday. My job was twofold. The dying are preoccupied fighting with death; the living are preoccupied fighting with life. I spent two years and three months watching how tenaciously people persist in clinging on to life.

Everybody’s gone. Everybody’s left you. You’ve been abandoned.

My father didn’t have anything to say. From the moment he became unable to eat food, his life’s flame began to flicker. He lost 30 kilograms worth of flesh, blood, emotion, and judgment. He was left with only traces of life: fingers which moved about sluggishly when I took his hand in mine. I forgot my father, my father who could no longer even swallow hate, while roasting steaks fresh with the smell of blood.

In the smell of urine and sound of moaning which hung in the hospital room, I looked into the mirror of my father’s face. I have to be shameless. My father couldn’t be, but I have to live what is left without shame. With a soul which has had the source of its pain removed, I must expertly avoid the arrow aimed to pierce me through.

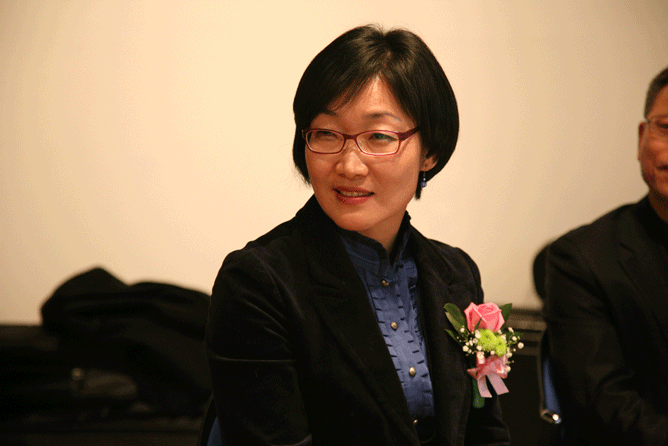

Choi Ok-Jeong (1964—) is the author of the short story collection House of Memory (기억의 집), winner of the 2001 prize for best new author. In 2009, she published Farewell, Chupa Chups Kid (안녕, 추파춥스 키드).

To read rest of “I Met an Old Woman”, visit Munjang Webzine.